Your cart is currently empty!

12 Dec TATTOO HISTORY (PART I)

by Marta Moreira and Astek

THE ORIGINS

Thanks to archaeologists, we know that the practice of tattooing the skin is as old as homo sapiens. The first scientific proof of this fact is a mummified body kept in the archaeological museum of the Italian city of Bolzano after being discovered in 1991 in the Ötzal Alps. Researchers counted up to 61 tattoos distributed on his body, preserved in ice for 5,300 years. Lines on the left wrist, on the lower back, and on both legs – precisely in those places where this prehistoric man suffered from arthritis, which suggests that already in the Neolithic era tattoos were attributed to magical or curative purposes.

There is sufficient evidence to trace the geographical and historical evolution of the art of tattooing that acquired different meanings in each of the civilizations in which it was established. We know, for example, that Egyptian priestesses of the 11th dynasty were tattooed, and that around 1,000 B.C. tattooing reached Africa and Asia from Europe.

It did not have the same connotations everywhere. In some civilizations it developed as a form of artistic expression to which they gave new colors and compositions, and in others, such as in Ancient Greece and Rome, it was used as a method of stigmatization. That is, to mark slaves and criminals. With Constantine I, the first Roman emperor who gave freedom of worship to Christians, began a period of prohibition that lasted throughout the Middle Ages.

JAMES COOK AND THE RETURN OF TATTOOING TO THE WESTERN WORLD (LATE 18TH CENTURY)

James Cook

Let’s take a leap in time to talk about the origins of modern tattooing. To do so, we must go to the South Pacific. Specifically to Tahiti, the largest island of French Polynesia. The legendary British navigator and explorer James Cook landed in 1769 in this paradisaical place and observed with curiosity the traditions of the natives. He wrote about the strange custom of painting their bodies with drawings of dogs, birds or geometric figures; indelible drawings that the Tahitians called tatu (“to strike”) and the Samoans called tátau. By phonetic derivation Cook transcribed that word into English as tattow, in which we can already glimpse the origin of the modern word tattoo (English), tatuaje (Spanish) or tatouage (French).

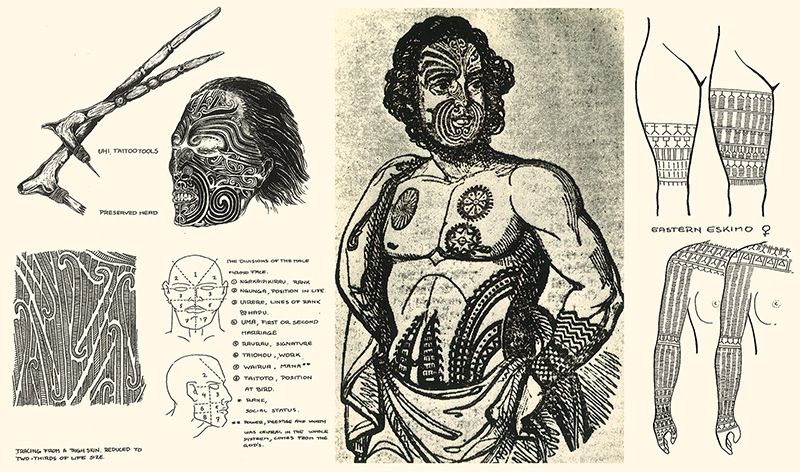

In his explorations in New Zealand, Cook also came into contact with the New Zealand Maori tribes, and observed how they also had the custom of adorning their bodies with ink. He was struck by the facial markings, a type of mark that referred to the family, lineage, social class or achievements of that person throughout his or her life. Just as women in Tahiti had their buttocks tattooed black when they reached sexual maturity, in Hawaii three dots on the tongue were a sign of mourning, and in Borneo an eye symbolized a spiritual guide to another life. It is entirely logical that this fascinating world of symbols and rituals was echoed in Europe by sailors returning from their voyages overseas. They were the link that allowed tattooing to gradually become popular among the general population of the Western world.

THE FIRST PROFESSIONAL STUDIOS

UNITED STATES: MARTIN HILDEBRANDT (1825-1890)

Martin Hildebrandt (1825-1890)

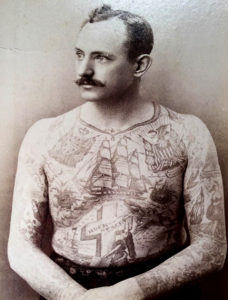

Although it is known that Native Americans have been using soot pigment or grinding minerals for tattooing since at least 1700, the popularization of the needle and ink in the United States reached its turning point during the American Civil War (1861-1865) with one undisputed protagonist: Martin Hildebrandt. During the war years this German-born sailor made a name for himself by tattooing both Union and Confederate soldiers. He used this prestige to open the first permanent tattoo studio in the country in 1875. It was located at 77 James Street in Lower Manhattan, New York. A city that was boiling with the incessant arrival of immigrants.

ENGLAND: SUTHERLAND MACDONALD (1860-1937) AND GEORGE BURCHETT (1872-1953)

Sutherland MacDonald (1860-1937) and George Burchett (1872-1953)

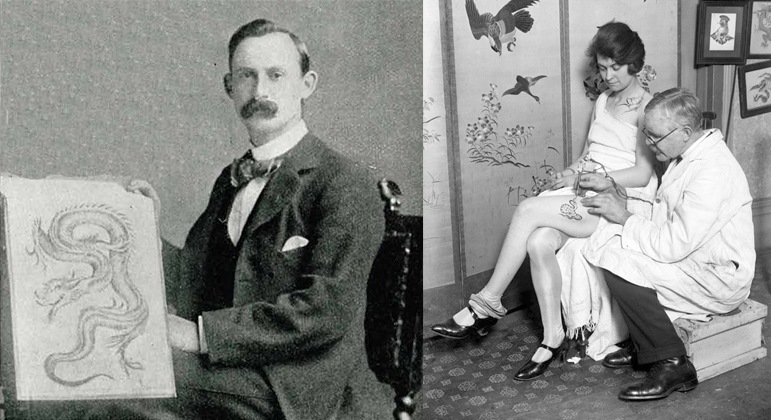

Fourteen years later than Martin Hildebrandt, a man named Sutherland Macdonald opened in London the first professional tattoo studio of the United Kingdom. It must have been quite a feat, considering that the inauguration took place in the midst of the Victorian era known for its repressive and moralizing character. Thanks in large part to Macdonald, tattooing went from being an absolutely marginal hobby to gaining the favor of royalty. Some historians point out that the decisive factor that made tattooing fashionable among European elites was the fact that King Edward VII of England and his son got tattooed in Jerusalem and Japan.

Macdonald reportedly tattooed several of Queen Victoria’s children, as well as the kings of Norway and Denmark, among other famous clients. “For nearly forty years, members of the nobility and other famous people climbed the narrow stairs of Jermyn Street to visit Macdonald and leave on their skin some of the most beautiful ornaments ever seen” wrote George Burchett in his 1953 book Memoirs of a Tattooist.

This pioneer’s legacy also includes the patenting of an electric tattoo machine in 1894, as well as the introduction of blue and green in his work. An 1897 article in the Strand magazine, written by Gambier Bolton, stated that “for shading or heavy work, Macdonald still used Japanese tools and ivory handles.” In other words, he was a key figure in bringing sophistication to the art of tattooing.

George Burchett, twelve years younger than Macdonald, was considered one of the most famous tattoo artists in the world during the years he was active: from 1890 to 1953. He was born in the seaside town of Brighton, but developed his career in London, first on Mile End Road, and then at 72 Waterloo Road. In addition to being a star of the trade during the two world wars, he was the tattooist of choice for European royalty and the bourgeoisie. Among his clients were Frederick IX of Denmark, George V and King Alfonso XIII of Spain, grandfather of Juan Carlos I.

Burchett, who had trained with Tom Riley and the aforementioned Sutherland Macdonald, had served in the Navy, which gave him the opportunity to expand his usual repertoire of designs with motifs “borrowed” from Africa, Japan, or Southeast Asia.

TECHNOLOGY AND TATTOOING: THE FIRST MACHINES

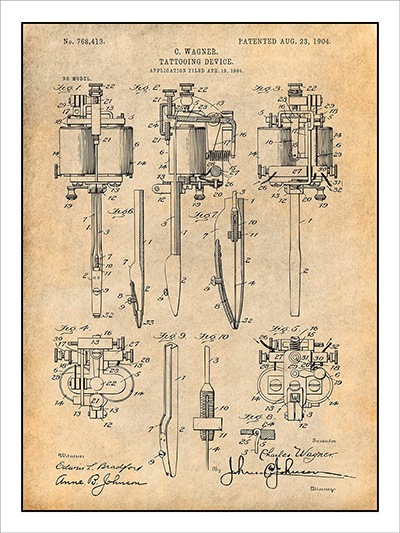

The patent of Charles Wagner

Along with the evolution of motifs and artistic resources applied to ink on the skin, the history of tattooing is also that of its technological development. Until the invention of the first electric machine, tattooing was done using rudimentary and artisan methods learned from primitive tribes in different parts of the world. The Maoris, for example, used chisels to open small wounds through which the ink penetrated. In Thailand, Polynesia, or Egypt they used small needles made of hollow materials that were sharpened, such as bamboo or albatross bones.

The first tattoo machine has an Irish name although its creator was the son of immigrants born in Connecticut in 1854. Samuel O’Reilly was inspired by the prototype of the rotary press invented by Thomas Edison, which was a kind of pen driven by an electric motor that punched paper to create a stencil for copying several documents at once. In 1891, O’Reilly realized that Edison’s invention could be used, with a few changes, to tattoo skin. His machine was a total revolution because it increased speed and reduced pain.

But, of course, there was room for improvement. That first machine was quite heavy, which complicated its use. This model evolved into a more efficient one that included two electromagnetic coils, springs and contact bars. At the beginning of the 20th century, Charles Wagner further improved the latter model. He added to the original design two electromagnets placed perpendicular to the position of the artist’s hand. It also allowed for easy needle changes, and had other conveniences similar to those of modern tattoo machines, as it allowed the ink flow to be regulated and the needle to be stabilized.

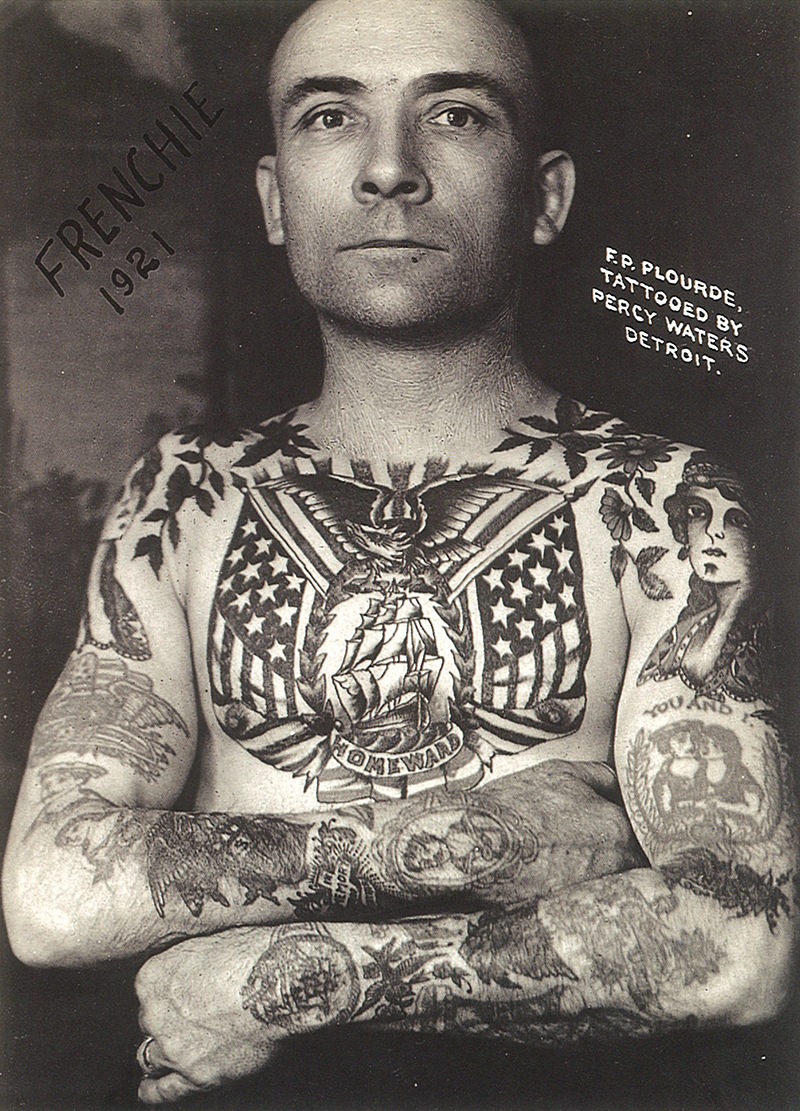

Tattoos made by Percy Waters

Patents followed one after the other during the thirties, but the name of Percy Waters stands out above all. In 1920, he manufactured the first modern tattoo machine by placing the two electromagnets parallel to the tattooist’s hand.

FIRST FEMALE REFERENCES OF TATTOOING

We cannot talk about the precursors of tattooing without talking about women. The first ladies of tattooing were linked to the circus world. The contemplation of the indelible drawings on the skin was a spectacle in itself for the society of the early 20th century. The bigger the act, the more exotic the motifs, and the more fanciful the accompanying stories, the more they paid and the more tickets were sold.

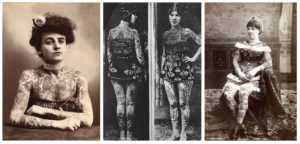

Maud Stevens, Nora Hildebrandt and Irene Woodward.

Maud Stevens (1877-1961) was a Kansas trapeze artist living in a wagon when she met Gus Wagner, a sailor and tattoo artist who had learned the trade on his travels in Java and Borneo. More than three hundred tattoos marked his skin when they met. They say she agreed to date him in exchange for him teaching her how to tattoo. That’s how she became Maud Wagner, master of the hand poked technique – she preferred the traditional method, even though the electric machine already existed at that time – and the first professional tattoo artist in history. She also turned her own body into a canvas covered with floral and zoological motifs, and words.

Maud was the first tattoo artist, but not the first woman famous for her total surrender to the art of tattooing. That recognition goes to Nora Hildebrandt, daughter of the pioneer Martin Hildebrandt, whom we talked about at the beginning of this article. Since she was a child, her father used her to practice, so that by the time she was 30 years old she had 365 tattoos all over her body. She found her professional destiny in the circus with a very important company of the time, Barnum & Barley, with which she embarked on continuous tours in the last decade of the nineteenth century.

But a 19-year-old Irene Woodward eclipsed Nora’s fame, seemingly quite suddenly. Irene, who also had her entire body tattooed, immediately captured the media’s attention, unseating her predecessor. The New York Times described her as an open-minded and very beautiful woman whose 400 tattoos wove a personal story of freedom and hope. In 1890 she made her international debut on a tour in Europe, exporting the fame of the “tattoo ladies” across the Atlantic.